The Lie of Travel

During my time living in Saut, I frequently walked with friends around the perimeter of the village, gazing off into the distance and observing other villages on nearby mountain ridges. On clear mornings, I could see smoke rising through the grass roofs of the homes in the neighboring village of Lemang as its residents cooked breakfast. On clear afternoons, my friends used mirrors or smoke—or they whistled particular tunes—to communicate across the ravine. If the canyon hadn’t been between us, I would have been fooled into thinking Saut and Lemang were the same place. Family ties were strong between them. Their histories were shared. Their language was identical.

Here’s what’s strange though. In order to actually visit Lemang, I had to hike down 2,000 feet in elevation, cross a river, and then hike back up to a mile high in elevation. Healthy villagers could make the trek—crossing waterfalls, descending vines, traversing dense rainforest, rebuilding broken bridges, scrambling over steep rock faces—in about three hours. Even though the two villages could communicate with whistles and smoke, it was an all-day affair to shake hands with one another.

During those arduous hikes, I listened as young boys retold the history that connected the two villages. They’d remind me of important names and warn me about topics to avoid. Basically, we used the travel time to approach Lemang as learners. On the surface, Lemang looked just like Saut, but over time, these two separated communities had grown apart in various ways as they established different habits and developed different values. For example, Lemang learned to appreciate decorating their houses, because its younger residents made frequent trips to town to buy batteries. They used the battery acid to decorate the bamboo panels of their houses. Lemang also learned to build complex bamboo water distribution systems, because at some point their distance from clean water had led to the death of numerous people.

Saut, on the other hand, was older, more established, and overflowing with natural spring water. They spent their time caring for what they already had, rather than engineering new things. The two villages were different and, increasingly, so were the people. Those long hikes prepared me to approach Lemang village as another culture. The longer I lived in Saut, the more I valued the physical distance which separated those communities. I needed that travel time to prepare to understand those people.

Our helicopter flights out of Saut were always bewildering, because as we rose higher and Saut grew small beneath us, we could quickly see dozens of other villages speckled across mountain ridges. Once, we landed in one of those villages to carry supplies to another translator. Villagers mentioned that it had taken them a difficult three days to make that journey by foot. Much to my shock, our flight had lasted less than five minutes! Five minutes by helicopter, or three days by foot.

In reality, I wasn’t a short five-minutes away from them. I was years away from being able to enter into the villagers’ world with understanding. It takes much longer to arrive at a culture than a place.

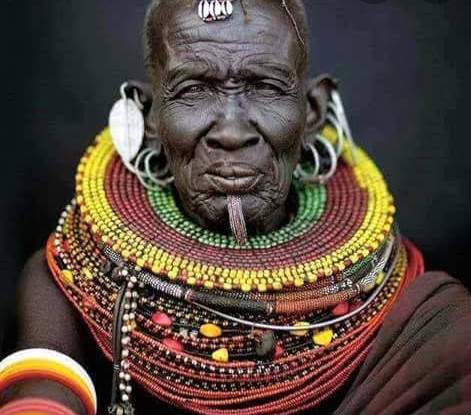

Throughout our time in PNG, I frequently confronted that strange reality of modern travel. We’d travel across the entire planet, from Houston to Los Angeles to Sydney to Port Moresby… . In less than a day, we would be using a different currency in a different land with different foods. But beneath those shallow representations of culture, we faced the much deeper differences of a world that valued group identity over individualism and people who did not compartmentalize their spiritual lives from their physical bodies.

Papua New Guinea is, in an infinite number of ways, a different world than America. It took us many years to be capable of standing on our own two feet there. We had to learn to understand their language and appreciate their customs. We had to face culture shock and adjust our value systems in order to survive. Those lessons are difficult and painful!

In the past, travelers had many months of travel by sea to adjust their hearts before arriving halfway around the world. Even then it wasn’t enough. They still had to navigate through all the other lessons. The speed of modern travel can fool us into thinking that physical distance is the greatest obstacle to ‘arriving.’ It absolutely is not. Learn to recognize that just because you have physical access to someone, does not mean you have made the whole journey into their world. To fully arrive we have to holistically travel, not just in body but in mind and in heart.