See

The last item on the pre-takeoff checklist was complete. I peered over the long snout of the Pilatus Porter only to see that the restless clouds had again closed off the narrow exit to the Omban valley.

The trouble with Omban is that the steeply down-sloping airstrip points directly at a mountain wall. The valley takes a hard right turn at the end of the strip but, from the takeoff position at the top of the airstrip, all I could see was the wall. Shutting down, I decided to walk to the bottom of the airstrip and take a peek around the corner into the exit valley.

The trouble with Omban is that the steeply down-sloping airstrip points directly at a mountain wall. The valley takes a hard right turn at the end of the strip but, from the takeoff position at the top of the airstrip, all I could see was the wall. Shutting down, I decided to walk to the bottom of the airstrip and take a peek around the corner into the exit valley.

Right: Looking down the Omban airstrip on a fair weather day.

Standing at the edge of the cliff at the end of the runway, I peered around the corner—the valley was actually open quite nicely. I picked out a landmark on a ridge that I knew I’d be able to see from the top of the airstrip, turned around, and hiked back up to the airplane.

Arriving back at the top, I turned around, and to my chagrin, my go/no-go landmark was now enveloped in clouds. Ah well, when these mountains call for patience, patience is what I give them. My passengers were being extremely patient as well, agreeing to stay belted in their seats in anticipation of a brief window of open skies.

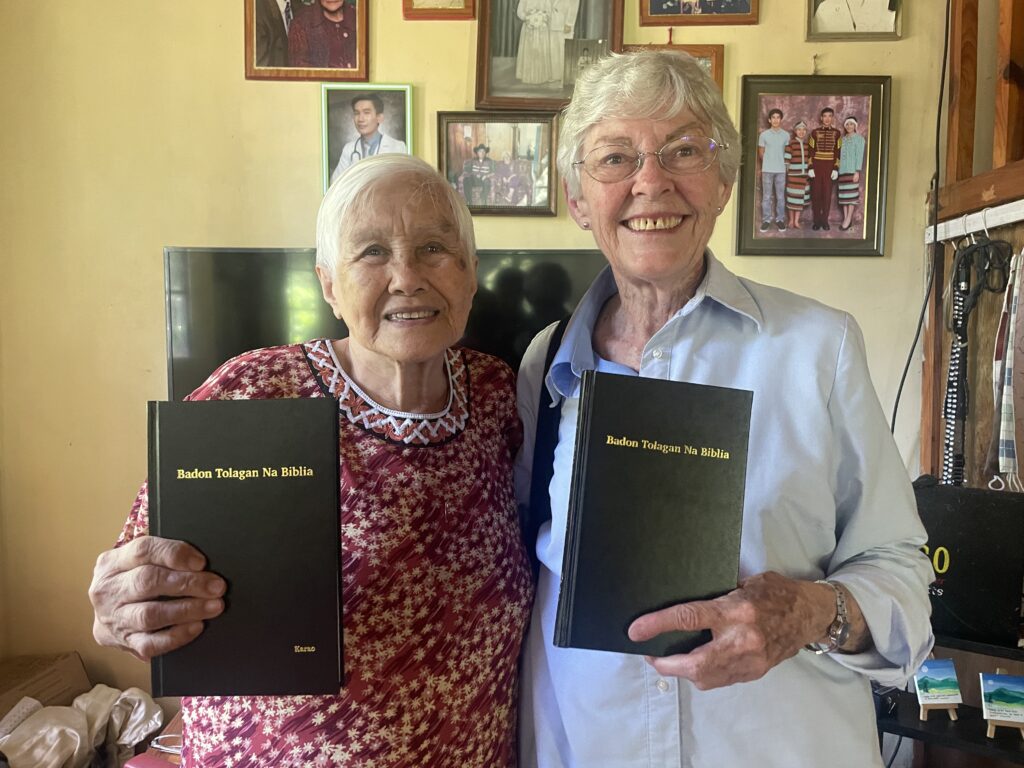

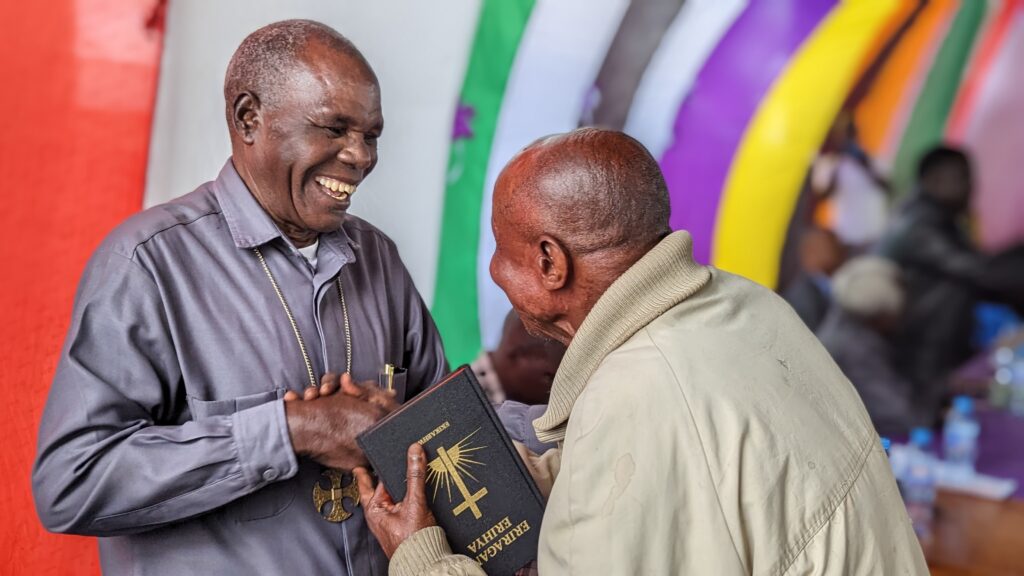

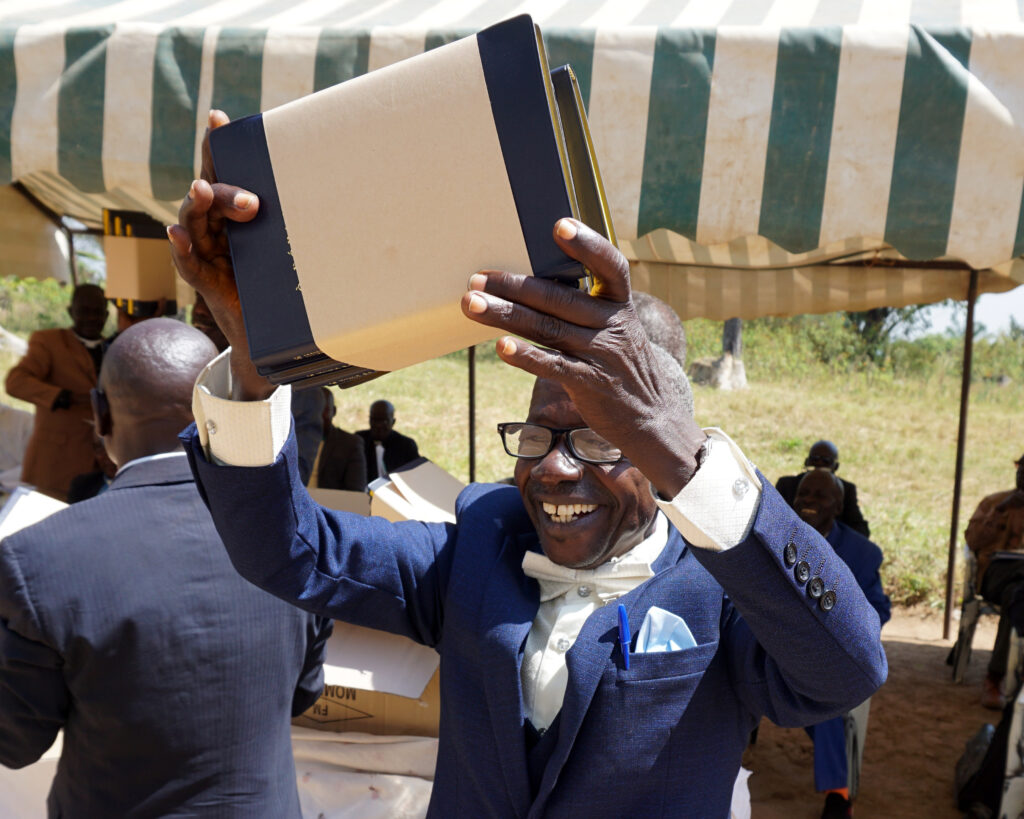

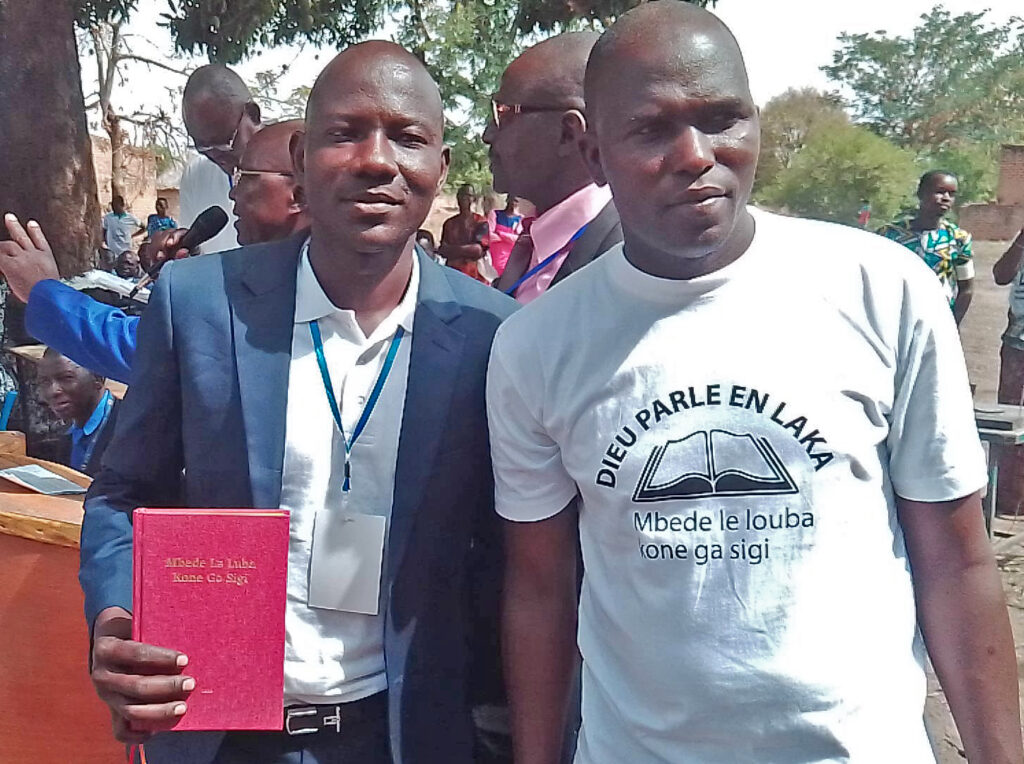

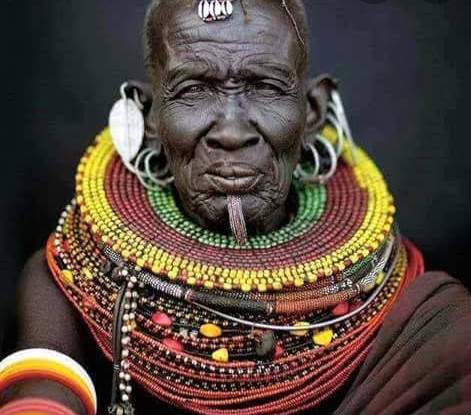

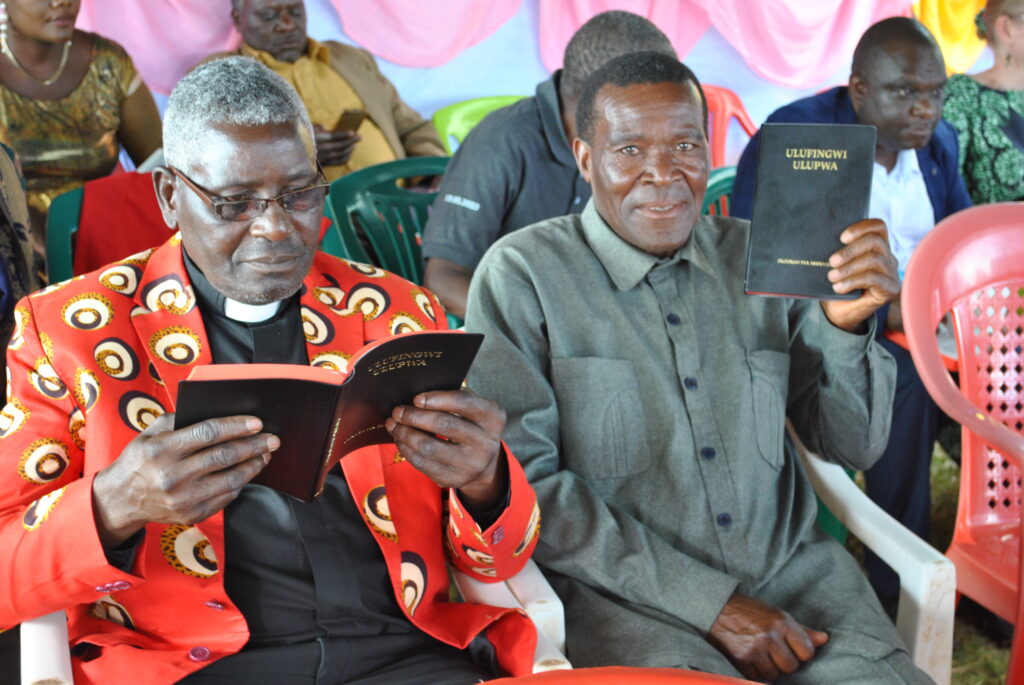

Forgive me … I should have introduced you to my passengers earlier. Andrew and Anne Sims have been working on translation in Papua’s Star Mountains for more than 25 years. This particular week we were trying to pull off something that we’d never done before: Scripture dedications in three separate mountain locations—two different language groups—in a single week. The first dedication had been held in Omban two days prior. Now a huge gathering was waiting in nearby Okbap for Andrew and Anne to arrive (along with two planeloads of guests) so that their celebration could begin. Only thing was, we were trapped in Omban.

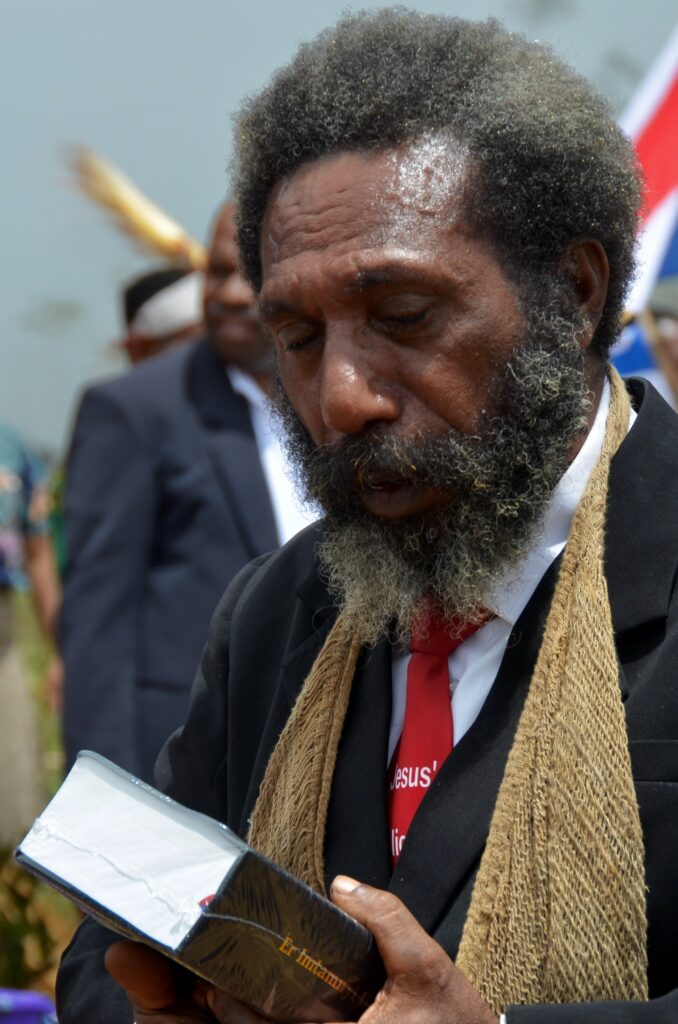

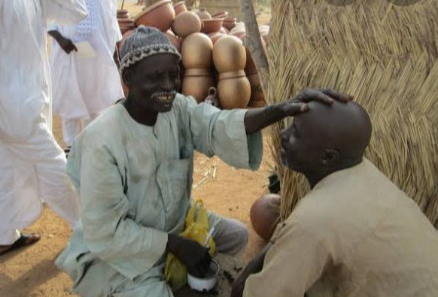

At the side of Omban’s airstrip, a group of Ketengban were sitting, watching and waiting with us. Softly, one of the men in the group called over to me, “Hey, we’re gonna pray if that’s OK.”

I’m sure they’d been waiting patiently for one of us “professional” Christians to think of it. Eventually their patience ran dry. Somebody had to do this.

For several minutes this simple tribal man spoke fervently to the God he believed could understand his Ketengban sentences. The only words I understood were my name (probably in the context of, “Lord, forgive the idiot pilot who forgets to pray”) and the Indonesian words for airplane and weather. And, of course the word Amen, which, when uttered, was the signal for them all to open their eyes and look down the mountain slope to the valley’s clogged mouth … only, it wasn’t clogged anymore. A just-wide-enough opening had appeared, and my all-important landmark was clearly visible. “See,” he said to me. Not a lot of emotion—just rock-sure faith that the Creator his new Book spoke of listens to his creation. Pointing, he said, “God opened the weather for you.”

I sputtered a thanks, climbed in, fired up, and took off, not sure if this particular answer to prayer came with an expiration time.

Recently, a friend asked what the highlight of those three dedications was for me. To be sure, I will always remember many moments from that week of watching the Ketengban and Lik people celebrate God’s Word in their own language, but the most powerful moment was a quiet one: having men of faith pray for us–and watching God answer that prayer.